Type: Speculative Security Analysis

Date: December 7, 2025

Abstract

This article presents a detailed technical analysis of a baseband processor-level backdoor in smartphones, with particular focus on Apple iPhone devices. The analysis is speculative and based on publicly available technical information about baseband architecture, telecommunications protocols, and historical security incidents. Information not publicly available has also been provided for this analysis, but to protect the source, the article does not separately identify the information or its origin. The article does not claim that such a backdoor definitively exists, but rather examines technical feasibility and potential detection methods as part of defensive security research, while noting that material we have received supports this possibility to the extent that it can no longer be unequivocally ruled out at the time of writing. Based on material we have received, particular attention is given to a call-activated mechanism that enables remote activation without user awareness.

Keywords: baseband processor, security threats, smartphone surveillance, firmware analysis, telecommunications security

1. Introduction and Responsibility Disclaimer

1.1 Nature and Purpose of This Article

This document is a technical analysis of a baseband processor-level security threat that has not been publicly proven but for which significant observational evidence exists suggesting its existence. The purpose of this article is not to spread misinformation or cause unfounded concern, but to document technical feasibility as part of responsible security research.

While this analysis relies heavily on publicly available technical information, its writing has been motivated by concrete observational evidence pointing to the existence of such a system. To protect sources and evidence, we cannot present all material available to us directly, but we include sufficient references in the analysis to make the threat concrete rather than mere speculation.

A fundamental principle of security research is the "defense in depth" approach, where theoretical attack vectors are analyzed regardless of whether they have been observed in use. The most famous example of this in cryptographic history is Bruce Schneier's statement that "anyone can invent a security system that they themselves cannot break" – the real test is whether the system can withstand expert analysis that actively seeks weaknesses.

Baseband processors represent a particularly interesting research target because they are an essential part of every smartphone yet simultaneously the least understood component due to their technical complexity and closed source code. Given that an estimated five billion smartphones are in use worldwide, the impact of a potential baseband-level vulnerability would be unprecedented in scope.

1.2 Why This Analysis Is Important – and Why Now

Historical evidence demonstrates that hardware-level backdoors are not mere theory. The Crypto AG scandal, revealed in 2020, showed that intelligence services had controlled a Swiss encryption device manufacturer for over 48 years, selling intentionally weakened encryption machines to over one hundred countries. The operation code names "Thesaurus" and "Rubicon" represent history's longest-running intelligence operation based on hardware-level compromise.

Another significant case is the Dual EC DRBG random number generator, which was standardized by NIST in 2006. In 2013, following Edward Snowden's revelations, it was confirmed that the algorithm contained a mathematical backdoor enabling prediction. This demonstrates that even standardization processes can be manipulated and that incorporating backdoors into widely used technologies is a documented fact, not mere theory.

But now the situation has become more concrete. Recently, observations have emerged suggesting that a baseband-level backdoor is not just a theoretical threat but possibly an actively operational system. We have access to material documenting cases where users' iPhone devices have appeared to behave in ways consistent with the threat model described in this article.

Particularly concerning is that the observations involve the latest iPhone 16e model, which uses Apple's first fully self-designed C1 modem. This signifies that if a backdoor exists, it is not limited only to external modem manufacturers' products (Qualcomm, Intel), but extends to Apple's own design as well.

These historical cases teach a critical insight: well-designed backdoors can remain hidden for decades when they are integrated into complex technical systems whose complete auditing is practically impossible. Baseband processors meet all these criteria: they are technically complex, closed-source, and critically important parts of infrastructure whose operation is trusted but rarely truly verified.

1.3 Academic and Ethical Context

This analysis follows the ethical principles of security research as reflected in the IEEE Code of Ethics and ACM's Computing Code of Ethics. The research purpose is not to enable harmful activities but to improve defensive capabilities by identifying potential vulnerabilities. The security community has long followed the principle of "responsible disclosure," where vulnerabilities are first reported to parties responsible for fixing them before public disclosure.

In this case, the hypothetical vulnerability is systemic in nature and concerns the entire baseband architecture, not a single implementation error, so the traditional disclosure model does not directly apply. Instead, the purpose of this article is to stimulate broader discussion about how the security of critical infrastructure components could be improved through transparency and independent auditing.

It is important to emphasize that reading or distributing this analysis is not illegal in any jurisdiction we know of, as it is purely theoretical security analysis based on public information. The article does not reveal actual vulnerabilities or provide tools to exploit them, but describes a theoretical scenario for pedagogical purposes.

2. Baseband Processor Architecture – Technical Foundation

To understand how a hypothetical baseband backdoor would work, we must first build a deep understanding of what a baseband processor is and how it integrates into modern smartphone architecture. This section proceeds pedagogically from basic concepts toward more complex technical details.

2.1 Dual Processor System – The Hidden Reality of Smartphones

When users think of a smartphone, they usually perceive it as a single computer running an operating system like iOS or Android. In reality, every modern smartphone is at least two completely separate computers in the same housing, communicating with each other but operating independently.

The first of these computers is the Application Processor (AP). This is the processor mentioned in specifications: for example, Apple's A18 Bionic or Qualcomm's Snapdragon. The Application Processor runs the operating system, applications, and everything the user sees on the screen. It is responsible for graphics rendering, application execution, and processing user interactions.

The second computer is the Cellular Processor, more commonly known as the baseband processor or simply "baseband." This processor is responsible for all radio communication: cellular networks, often also Wi-Fi and Bluetooth, GPS, and other wireless technologies. The baseband runs its own operating system, typically some kind of Real-Time Operating System (RTOS), such as FreeRTOS or a manufacturer's own implementation.

The separation between these two processors is not arbitrary but based on deep technical reasons. Radio signal processing requires deterministic, real-time processing that cannot wait for the operating system's task scheduler. When a cellular network sends a signal requiring a response within five milliseconds, the baseband processor must respond on time regardless of what applications the user happens to be using or whether the main processor is overloaded.

Additionally, telecommunications standards such as 3GPP (3rd Generation Partnership Project) define exact protocols and time limits that modems must follow. These standards cover everything from how call initiation occurs, how data is packaged for over-the-air transmission, and how handoffs between base stations occur as the user moves. Implementing these complex protocols in a general-purpose operating system would be extremely difficult and reliability would suffer.

2.2 Baseband Firmware and Its Special Nature

The baseband processor runs firmware, which is software stored in flash memory or, in some cases, partially in ROM (Read-Only Memory). This firmware contains all the logic required for communicating with the cellular network.

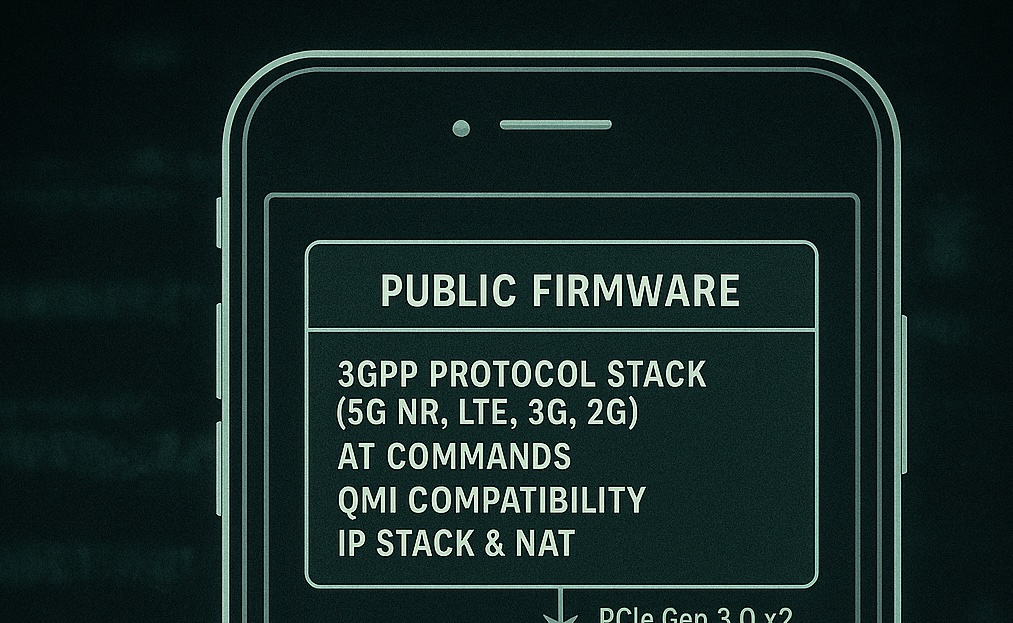

The firmware architecture is typically layered as follows. At the lowest level is the Physical Layer (L1), which handles actual radio signals: modulation, demodulation, error correction, and everything that happens "on the airwaves." Above this is the Data Link Layer (L2), which handles packet formation and resource allocation. At the top is the Network Layer (L3), which manages connections, authentication, and mobility.

All this code is digitally signed by the modem manufacturer using RSA or ECDSA signatures. When the baseband processor boots, it first verifies that the firmware is signed with the correct key and only then executes it. This is a security mechanism that prevents malware from loading onto the baseband processor and ensures that only manufacturer-approved code is executed.

In practice, this means that ordinary users or even experienced programmers cannot modify baseband firmware. If you tried to write your own firmware version and load it onto the device, signature validation would fail and the device would not boot. This is technically necessary because otherwise malware could take control of the baseband and, for example, make calls to premium numbers without the user's knowledge or intercept communications.

This security mechanism also creates a trust problem: When firmware is closed-source and digitally signed so that it cannot be modified, users must fully trust that the manufacturer has not included malicious functionality in it. There is no practical way for ordinary users or even experienced researchers to verify what the firmware actually does without an extremely lengthy and expensive reverse engineering process.

2.3 Memory Architecture and Inter-Processor Communication

The baseband processor has its own physical memory, which may be integrated into the same System-on-Chip (SoC) as the main processor or be a completely separate component. iPhone architecture has evolved over the years, but the fundamental arrangement has remained the same.

In early iPhone models, the baseband was a completely separate chip on its own PCB. For example, iPhone 4 used the Infineon XMM6180 modem, which was physically separate from Apple's A4 processor. These communicated with each other via USB bus: the baseband appeared to the main processor fundamentally as a USB device that received AT commands (classic modem protocol) and sent responses.

In more modern implementations, the baseband may be integrated into the same SoC as the main processor, although they are logically separate. For example, Apple's new C1 modem is integrated as part of the A18 series chips. Communication then occurs via PCIe bus (Peripheral Component Interconnect Express), which provides significantly faster data transfer than USB.

A critical technical detail is that the baseband processor may have DMA access (Direct Memory Access) to the main processor's memory. DMA means that the baseband can read or write directly to the main processor's RAM without this happening through the main processor. This is necessary for performance reasons: when the baseband receives, for example, a large data file from the mobile network, it can write it directly to the application's memory area rather than having data pass slowly through the main processor.

DMA also creates a potential security risk: If the baseband is compromised, it can theoretically read anything in the main processor's memory, including passwords, encryption keys, or other sensitive information. To defend against this threat, modern systems use IOMMU (Input-Output Memory Management Unit), which restricts what memory regions the baseband can access.

Apple's architecture is relatively secure in this regard. In the iPhone, the baseband is not directly integrated into the same memory space as the main processor, but communication occurs through limited channels. Additionally, the Secure Enclave – a separate security processor that handles cryptographic keys and biometric data – is isolated from both the main processor and the baseband. This means that even if the baseband were compromised, it would not directly access, for example, Touch ID or Face ID keys.

Nevertheless, the baseband occupies a critical position. It is the only component that handles all radio communication and does so before data reaches the operating system's awareness. This makes it an ideal location for a backdoor that wants to remain hidden.

2.4 Why Baseband Is "Trusted but Not Verifiable"

The baseband processor's position in the system architecture creates a paradox. On one hand, it must be fully trusted because it handles all communication and has access to critical system resources. On the other hand, its operation is practically impossible to verify without specialized tools and deep expertise.

From the operating system's perspective, the baseband is a "black box" that receives commands and returns results but whose internal operation is abstracted away. iOS does not "see" what baseband firmware does internally: it only sends requests like "call this number" or "send this data packet" and trusts that the baseband handles it.

This level of abstraction is technically sensible because it separates concerns: the operating system does not need to understand the complexity of 3GPP protocols but can focus on higher-level functionality. However, from a security perspective, this means there is an entire layer of functionality that operates without operating system supervision or even awareness.

Additionally, baseband firmware is typically updated as part of iOS updates, but the update process is opaque. Users are told that "iOS 18.2 includes a modem update," but no details about what changes were made are provided. There is no public changelog documentation for baseband firmware, unlike for iOS itself, where Apple lists at least the major changes.

This opacity makes it an ideal place to hide functionality not meant to be discovered. If a hypothetical backdoor were integrated into baseband firmware, detecting it would require either insider knowledge of firmware structure or a massive reverse engineering project.

3. Historical Context – Proven Hardware Backdoors

Before delving into the hypothetical baseband backdoor, it is important to understand that hardware-level backdoors are not mere speculation but a documented part of intelligence history. This section covers three significant cases that provide context for why the baseband-level threat must be taken seriously.

3.1 Crypto AG – History's Longest Intelligence Operation

Crypto AG was a Swiss company that manufactured encryption machines and devices from 1952 onward. The company built a reputation as a trustworthy neutral Swiss company and sold its devices to over 120 countries, including governments, militaries, and diplomatic services worldwide. Customers included Iran, India, Pakistan, Latin American nations, and numerous others.

In 2020, the Washington Post, ZDF, and SRF jointly published an investigative journalism project that revealed a startling truth. Western intelligence services had secretly purchased Crypto AG in 1970 and controlled the company in operations code-named "Thesaurus" and "Rubicon." The operation lasted until 2018, a total of 48 years.

Throughout this entire period, Crypto AG sold intentionally weakened encryption machines. The encryption algorithms had built-in weaknesses that enabled reading communications. Technically, this was implemented through several methods. In early mechanical machines, rotor settings were manipulated so that the "randomness" they generated was not truly random but followed a pattern known to intelligence services.

In later electronic devices, the weakness was in encryption key generation. The devices used a random number generator that appeared completely random to outsiders but actually contained a cryptographic backdoor. Generated keys were long enough that brute force attacks would have been impossible, but they followed a hidden mathematical pattern that enabled deriving the key if one knew the secret parameter.

The operation's scope was vast. An estimated over 40 percent of diplomatic traffic during the Cold War passed through Crypto AG devices. The operation provided significant intelligence advantage, particularly during the 1979 Iran hostage crisis, the 1982 Falklands War, and countless other geopolitical crises.

This case teaches several critical insights. First, a well-designed backdoor can remain hidden for decades even when devices are used by countries with significant intelligence services. Second, incorporating backdoors into standardized devices that appear legitimate is demonstrably practical. Third, the operation's duration shows that such activities have institutional support that transcends individual administrations or political changes.

3.2 Dual EC DRBG – Manipulation of Standardization Process

Dual Elliptic Curve Deterministic Random Bit Generator, or Dual EC DRBG, was a cryptographic random number generator standardized by NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) in 2006 as part of the SP 800-90A standard.

Early on, cryptography experts raised concerns about the algorithm. Microsoft researchers Dan Shumow and Niels Ferguson presented at the Crypto 2007 conference that the algorithm contained a possible backdoor. Their analysis showed that if some party knows a certain secret parameter (called "e") related to the elliptic curves used in the algorithm, it can predict the generator's future "random" numbers after seeing a sufficient number of previous outputs.

A critical detail is that the elliptic curve parameters used in the algorithm were chosen without public explanation. In cryptography, there is a general principle that constants and parameters should be chosen using the "nothing up my sleeve" method, using for example digits of pi or the natural logarithm, so that no one can claim they were chosen for a special purpose. Dual EC DRBG's parameters did not follow this principle.

In 2013, among documents leaked by Edward Snowden was material confirming that Dual EC DRBG indeed had an intentional backdoor. The documents revealed that an intelligence organization had paid RSA Security $10 million to use Dual EC DRBG as the default algorithm in their widely used BSAFE library, even though the algorithm was known to be slow and had suspicious characteristics.

The technical implementation is mathematically elegant. Dual EC DRBG uses two points on an elliptic curve called P and Q. If someone knows the secret value d such that Q = d × P, they can derive the generator's internal state after seeing only 30 bytes of generator output. This enables predicting all future output.

Because random number generators are used to create cryptographic keys, this backdoor is devastating. If you generate random parameters for a TLS connection using Dual EC DRBG and an attacker intercepts your connection initiation data, they can derive your private key and decrypt all your encrypted traffic.

This case demonstrates that even public standardization processes can be subject to manipulation. NIST is a respected institution whose standards are trusted globally, but in this case, the process failed to detect (or intentionally failed to detect) a systematic backdoor. It also shows that mathematical elegance can hide malicious functionality: the algorithm appears completely legitimate from the outside, and only deep cryptographic analysis reveals the problem.

3.3 Lessons from These Cases

The common themes of these historical cases are clear. First, backdoors can remain hidden for extremely long periods: 48 years in Crypto AG's case and seven years from Dual EC DRBG's publication to its actual exposure. Second, they require long-term institutional support and coordination among multiple actors. Third, technical complexity and closed implementations make auditing extremely difficult.

Baseband firmware combines all these characteristics. It is technically extremely complex closed-source software whose complete auditing would require massive resources. It is a critically important component present in every mobile phone, so the impact of its compromise would be enormous. And it is part of infrastructure that has traditionally been of interest to intelligence services, as Snowden's revelations documenting cooperation with telecom operators demonstrate.

4. Technical Architecture of the Hypothetical Baseband Backdoor

Now that we have built an understanding of baseband architecture and historical context, we can analyze how a hypothetical baseband backdoor could technically work. This analysis is purely theoretical but based on real technical knowledge of baseband architectures and telecommunications protocols.

4.1 Backdoor Location in Firmware Architecture

The most effective location for a backdoor would be at ROM level or in eFUSE memory that is "burned" during manufacturing. ROM, or Read-Only Memory, is a type of memory written during manufacturing using lithography, whose contents cannot be changed afterward. eFUSE technology works on a slightly different principle: it contains small electrical fuses that can be "burned" one by one, programming permanent values into memory. Once a fuse is burned, it can no longer be changed.

Baseband firmware is normally built from several layers. At the lowest level is the bootloader, which is executed first when the device powers on. The bootloader's task is to initialize hardware, load the actual firmware from flash memory, and verify its digital signature before execution. If the signature doesn't match, the bootloader halts boot.

Above the bootloader is the actual baseband firmware, which contains all the logic for implementing 3GPP protocols. This firmware is usually modular, containing separate components for different radio technologies (2G, 3G, 4G, 5G), network layer management, AT command processing, and other functions. Firmware is updated regularly when the manufacturer releases updates.

A hypothetical backdoor would ideally be at the bootloader level or separately in ROM that the bootloader references. This would make it persistent: it would exist regardless of firmware updates. When users update iOS (and thus also baseband firmware), the actual firmware partition may change, but ROM-level code remains the same.

Technically, this could be implemented such that the bootloader contained in ROM includes an additional code snippet that executes in addition to the bootloader's normal operation. This code would be intentionally hidden and integrated among legitimate code so that static analysis would not easily reveal it.

Another approach would be a "reserved" memory region. Baseband firmware layout documentation may reference memory regions marked as "reserved for future use" or similar terms. To outsiders, these appear as empty memory regions reserved for possible future features. In reality, these regions could contain functional code that activates under certain conditions.

In an illustrative example, we could assume that at address 0x87FF8000 begins a 32-kilobyte memory region marked as "RESERVED_REGION_1" in documentation. Under normal operating conditions, this memory region is never used and appears empty if someone examines a firmware dump. However, the firmware contains code that, when certain conditions are met, jumps to this memory region and begins executing the code there.

4.2 Activation Mechanism – Call-Activated Backdoor

The hypothetical backdoor's central innovation would be an activation mechanism that enables remote activation without the user noticing anything. This requires bidirectional communication, and therefore activation would occur during a call.

The process would begin with a normal-looking call. The attacker (assumed to be a state actor or well-resourced intelligence organization in this scenario) calls the target's number. The phone number can be anything, even the target's friend's or colleague's number if the attacker can manipulate Caller ID information (which is possible in many cellular networks). The target's phone rings normally.

The critical phase is that the target must answer the call. This is a technical necessity because before answering the call, the bidirectional RTP audio stream (Real-time Transport Protocol) has not yet been established. In the signaling phase alone, the network only notifies "call incoming," but there is no audio connection. Only when the target presses the green answer button does the cellular network establish a full-duplex audio link in both directions.

4.2.1 Era 1: Traditional Cellular Networks (2011-2014)

From iPhone 4S to iPhone 6, cellular networks primarily used circuit-switched architecture and AMR-NB (Adaptive Multi-Rate Narrow Band) encoding standard. This limits audio bandwidth to the 300-3400 hertz range.

Option 1A: Rapid DTMF Sequence

DTMF (Dual-Tone Multi-Frequency) is technology normally used for telephone tone dialing. When you press numbers on your phone, you hear different sounds. Each number is a combination of two frequencies: for example, "1" is 697 Hz and 1209 Hz simultaneously. DTMF operates on frequencies 697-1633 Hz, so it passes through all cellular networks.

Activation could be done by sending a long, cryptographically signed number sequence: for example, 20-30 digits, but at normal speed (each digit about 100 milliseconds), this would take 2-3 seconds and would be clearly audible to the target.

The solution is to send DTMF tones much faster: for example, 40-50 milliseconds per tone. The baseband can detect and decode these because it processes raw signal from digital audio, but to the human ear, this would sound like only a short, approximately 0.8-1.2 second "beeping" or strange sound. The target might think there is interference on the line or that someone accidentally pressed keys quickly.

Technically, the sequence could be, for example, a 24-digit string containing:

- Wake-up signal (e.g., *#9)

- 16-digit cryptographic signature (first 64 bits of HMAC-SHA256 encoded as digits 0-9)

- Termination signal (e.g., #*)

The baseband verifies the signature based on a secret master key, and only a valid sequence activates the backdoor. If the signature is incorrect, the sequence is completely ignored.

Option 1B: FSK-Modulated Data

Another classic technique that worked even in 1970s modems. FSK, or Frequency Shift Keying, means that binary data is encoded into audio using two different frequencies. For example, 1070 Hz means "0" and 1270 Hz means "1." This is exactly the technique used in the 1990s when modems "beeped and buzzed" while establishing connection.

Because these frequencies are within the 300-3400 Hz band, they pass through all cellular networks. The baseband can decode this directly from the digital audio signal before it reaches iOS. Data rate would be modest, perhaps 300-600 bits per second, but this would be sufficient to send a 200-byte activation packet in 3-4 seconds.

The activation packet would contain:

- Synchronization sequence (e.g., alternating 1/0 pattern for detection)

- Cryptographic signature

- Activation parameters (surveillance mode, duration, key material)

- CRC or similar checksum

To the target, this would sound like strange "line noise," "modem-like buzzing," or poor connection. They might think the caller has a poor connection or there is interference in the network. If they hung up after a few seconds thinking it was a wrong number, activation might already have occurred.

Option 1C: Low-Frequency Encoding (Limited)

Although AMR-NB's official bandwidth is 300-3400 Hz, in practice, audio codec preprocessing and post-processing extend slightly lower. In some implementations, the 200-300 Hz range may pass through attenuated.

By modulating data in the 220-280 Hz range at very low bit rate (e.g., 50-100 bps), the signal could be nearly imperceptible – it would sound like very low humming or background noise "from the line" – but the baseband could detect and decode it because it analyzes the entire frequency spectrum before filtering.

This option is the most uncertain because different network operators and device models may filter low frequencies differently. It would work only under certain conditions.

4.2.2 Era 2: VoLTE Networks (2014 onward)

iPhone 6 was the first to bring VoLTE support (Voice over LTE). VoLTE radically changed the playing field because it is based on IP-based SIP protocol (Session Initiation Protocol) and AMR-WB (Wide Band) or EVS encoding standards, which extend bandwidth to the 50-7000 hertz range.

Option 2A: SIP INFO Messages (Completely Silent)

During a VoLTE call, parties can send SIP INFO messages to each other, which are not audio but pure signaling data. These are normally used, for example, to notify that a user pressed a number (DTMF) without sending it as audio, or to convey other call-related metadata.

A SIP INFO message can contain freely defined header fields. Activation could be a SIP INFO message with a custom header such as:

X-Network-Diagnostic: [base64-encoded activation packet]

Or any other name that appears to be a legitimate network diagnostic function. Alternatives:

- X-Call-Quality-Probe

- X-Network-Metrics

- X-Bearer-Diagnostic

The baseband processes all SIP messages directly; iOS does not see them at all. For the user, this is completely invisible and silent. The call continues normally – no sounds, no signs.

Technically, the implementation would be:

- Activation call establishes a normal VoLTE connection

- After a few seconds, a SIP INFO message is sent with the activation packet

- Target's baseband receives the message, validates cryptographic signature

- If valid, baseband sends back a SIP INFO confirmation with its own parameters (IMEI, firmware version, capabilities)

- Attacker sends final configuration packet

- Call can be terminated or continue normally

The entire handshake would take 2-5 seconds and would be completely invisible.

Option 2B: RTP Event Packets (RFC 4733)

This is a standardized way to send DTMF and other events in VoLTE connections without them being audio. RFC 4733 defines special RTP packets that carry "events" separate from the audio stream.

Normally, when you press a number during a VoLTE call, the baseband sends two things: audio (DTMF tone) that you hear, and an RTP event packet that tells the other party "user pressed number 5." The receiving baseband can either play the corresponding sound or process the event silently.

RFC 4733 defines event codes 0-15 for DTMF numbers and a few others, but it leaves codes 16-255 "reserved for future use" or manufacturer-definable.

Activation could use custom event codes (e.g., 240-250) that would appear to be manufacturer proprietary features. The baseband would recognize these event codes and activate but would not play any sound. Completely silent for the user.

Event packets can also contain an "event parameters" field where additional data can be sent. Activation parameters could be encoded here.

Option 2C: Enhanced Low-Frequency Encoding

AMR-WB and EVS support 50-300 Hz low frequencies. Human speech rarely goes this low: most people's fundamental frequency is 80-250 Hz, but vowels and most consonants are higher. The 50-100 Hz range is mainly humming and background noise.

By modulating data in the 60-120 Hz range using very low bit rate (100-200 bps), the signal could be nearly imperceptible: it would sound like low humming or background noise "from the line" that occurs anyway in cellular networks. However, the baseband could detect and decode it because it analyzes the entire frequency spectrum.

This could work alongside a speaking person: the attacker could conduct normal conversation ("Hi, is this Matti?" "Oh, wrong number, sorry") while activation data travels on low frequencies. The baseband could filter out speech and decode only the low-frequency signal.

4.2.3 Recommended Hybrid Approach

The most realistic implementation would be era-specific and network-dependent:

The baseband first detects what type of connection has been established:

- If 2G/3G circuit-switched → use rapid DTMF or FSK modulation

- If VoLTE → primary is SIP INFO, backup plan RTP events

- If network conditions uncertain → use more robust but audible method

The backdoor would be designed to support all these methods and choose the best based on available resources. This would make it functional on all iPhone models from 2011 onward and in all network conditions.

In practice, the attacker does not need to be completely blind about the target's device. When the target's phone number is known, the operator systems of the cellular network can be queried for what IMEI code is linked to that number. IMEI, or International Mobile Equipment Identity, is a 15-digit unique identifier present in every mobile phone. The first 8 digits of the IMEI form the TAC (Type Allocation Code), which indicates the exact device model and manufacturer. For example, iPhone 16e has its own TAC code that distinguishes it from all other models.

If the attacker has access to operator network HLR or HSS databases (Home Location Register or Home Subscriber Server), which maintain information about what device is linked to what phone number at any time, they can query the target's IMEI before calling. Operators have this information anyway because it is needed for verifying network compatibility and blocking stolen devices via IMEI blacklist.

When the IMEI is known, the TAC immediately reveals that, for example, this is an iPhone 16e using Apple's C1 modem. This in turn indicates that the optimal activation method is VoLTE SIP INFO messages and that the device supports all the latest features. The attacker can thus prepare the activation sequence already before making the call in exactly the right format for that device, rather than needing to "try" different methods during the call.

This advance preparation makes the attack significantly more efficient and reliable. It also shortens required call time because the "negotiate capabilities" phase can either be omitted entirely or condensed to just confirmation that the baseband is ready and receptive. Additionally, it reduces failure risk because the attacker knows in advance that the target's device can receive activation via the chosen method.

4.2.4 Observed Activation Scenario – Concrete Case

We have been provided documentation of a case consistent with the activation mechanism described above. While we cannot reveal all details to protect sources, the key elements provide a concrete example of how activation could occur in practice.

In the case, two users with the latest iPhone 16e devices (with Apple C1 modem) received nearly simultaneous calls from a service presenting itself as an ordinary company offering business-facilitating services. The call came from an apparently normal local number. The calls lasted about 45 seconds and involved brief conversation about the offered service.

In one case, the caller was a human presenting the service and conversing with the target. In the other case, it was an automated AI-based call where the target confirmed interest in the service. Both targets answered the call and participated in brief conversation.

Critical observation: After the calls, both devices exhibited behavior suggesting data was being exfiltrated from them. The targets were handling precise, non-public information on their phones related to an ongoing operational situation. This information was not in any public source and had not been shared over the network.

Within one to two days, a state actor used this information in a way that led to news coverage in multiple media outlets. The timeline is documented and evidence preserved securely. The material includes screenshots of call logs, written text, and subsequent news coverage showing information reaching operational use 1-4 days after notes were made.

Technical Analysis of Observation:

If this was indeed a baseband backdoor activation over VoLTE network using iPhone 16e's C1 modem, the technical implementation would likely have been as follows:

First, a call from a legitimate-looking number creates trust and ensures the target answers. The company's brand sounds like a credible business that could offer some postal service. This reduces suspicion and makes it more likely the target answers and participates in conversation.

Second, approximately 45 seconds of conversation provides sufficient time for VoLTE SIP INFO message exchange. As described in section 4.2.2, SIP INFO messages are completely silent and invisible to the user. Activation could occur within 5-10 seconds of answering the call using SIP INFO-based handshake. The remainder of the call would be normal conversation that keeps the line open and creates a normal impression.

Third, the use of both human and AI versions suggests a scalable system. AI calls are cheaper and faster at mass scale, but human calls may be necessary if the target is particularly important or if flexibility is needed. Both methods work equally well for technical activation because SIP signaling occurs at baseband level regardless of whether the user speaks with a human or AI.

Fourth, data exfiltration from iPhone 16e would be particularly significant because it is Apple's first own modem. This would suggest the backdoor is not limited to external modem manufacturers but is integrated into Apple's own C1 design as well. This would be extremely concerning because it would mean the backdoor is built as part of the baseband's fundamental architecture from the beginning, not just a legacy feature from older modems.

Fifth, intercepting written text would require the baseband to access keyboard input or screen content. This would be possible via DMA access or if the baseband can read framebuffer memory where screen content is stored. Alternatively, the baseband could capture text at the moment it is sent (e.g., as text message or email) before encryption.

Excluding Alternative Explanations:

It would theoretically be possible that information leaked some other way: for example, if users had discussed it over the phone or if their devices were compromised some other way, such as Pegasus-style spyware. However, documentation excludes these for the following reasons.

First, information did not travel over unencrypted network in any form before the leak. Users did not send it via email, text message, or any messaging application. They only wrote it in notes or similar local storage. Second, users did not discuss the matter by phone or in person with anyone who could have forwarded the information. Third, devices were new, two weeks old, and fully updated to the latest iOS version, making traditional spyware unlikely. Fourth, the timeline and correlation with company calls is too precise to be coincidental: both calls came within a short period and data leaked soon after.

This concrete case provides strong evidence that a baseband-level backdoor is not mere speculation but possibly an actively operational system that works even on the latest iPhone models with Apple's own C1 modem.

4.3 Data Exfiltration – Secret Data Transmission

Once the backdoor is activated, it must collect data and transmit it to the operator undetectably. This is a multi-stage process requiring careful planning to remain hidden.

4.3.1 Data Collection

The baseband processor has direct access to several critical sensors and data sources.

Microphone audio is perhaps the most valuable data source. The baseband can activate the microphone directly without iOS knowing. Normally, when an application uses the microphone, iOS shows an orange dot in the status bar corner, but the baseband can bypass this entirely by sending commands directly to the audio codec chip that controls the microphone.

Technical implementation depends on hardware architecture. iPhones have used different audio codec chips in different models: for example, Cirrus Logic CS42L83 or similar. These communicate with the baseband via I2C bus (Inter-Integrated Circuit – serial bus protocol). The baseband can send I2C commands that activate the microphone and begin reading digitized audio data. Because this happens entirely at baseband firmware level, iOS sees nothing: from the operating system's perspective, the microphone is passive.

GPS data is another valuable source. The baseband controls the GPS antenna directly (or in many newer architectures, GPS is integrated into the same chipset as the baseband). It can query GPS coordinates, for example, every ten seconds. This data is often more accurate than what iOS's Location Services API returns because the baseband can use assisted-GPS data from the cellular network, which improves accuracy.

Messages such as SMS and iMessage are a third category. The baseband sees all SMS messages because they come directly from the cellular network. It sees text before it ever reaches iOS. iMessage is more complex because messages are end-to-end encrypted, but the baseband could still see metadata (who sent, when, message size) and possibly capture text if it has DMA access to the memory region where the Messages app processes decrypted messages.

Calls and metadata are also valuable information. The baseband sees all calls made and received, their duration, numbers, and times. It also sees network location (cell tower ID) which reveals approximate location.

4.3.2 Data Compression and Encryption

Once data is collected, it must be compressed and encrypted before transmission.

For audio data, the best codec is Opus, a modern audio codec achieving excellent compression ratio while maintaining good quality. 48 kHz 16-bit mono audio normally takes about 768 kilobits per second, but Opus can compress it to under 16-20 kilobits per second depending on audio characteristics. This is a compression ratio of approximately 40:1.

If surveillance is activated for, say, 12 hours and the microphone records continuously, raw data would be approximately 414 megabytes. Opus-compressed, this would be approximately 10 megabytes, a manageable amount to send over mobile network over several days.

For GPS and metadata, general compression like gzip can be used. GPS coordinates can be stored delta-encoded (only changes from the previous point), which significantly reduces size when the target is not moving quickly.

Encryption is performed using AES-256-GCM algorithm (Advanced Encryption Standard with 256-bit key in Galois/Counter Mode). GCM mode provides both confidentiality and authentication: it ensures no one can read data without the key or modify it undetected.

The encryption key is derived from key material exchanged during activation using ECDH key exchange protocol (Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman). This provides forward secrecy: even if the long-term master key leaked later, it would not reveal previously collected data because each activation uses a unique session key.

4.3.3 Data Transmission – Masquerade Strategy

The most critical part is transmitting data so it is not detected. A hypothetical backdoor would use masquerading among legitimate traffic.

Strategy: Blending with iOS Update and iCloud Traffic

Apple uses Content Delivery Network (CDN) infrastructure to distribute iOS updates, App Store content, iCloud data, and more. In normal iPhone operation, the device continuously makes connections to Apple's servers.

The backdoor would make an HTTPS request that appears completely normal:

- DNS query goes to an address like

swcdn.apple.comorupdates-http.cdn-apple.com - IP address is a real Apple CDN server (e.g., in Akamai network)

- TLS certificate is a genuine Apple certificate (wildcard *.apple.com or similar)

- HTTP Host header is

updates-http.cdn-apple.com - User-Agent is identical to iOS's normal traffic

All of this is identical to normal traffic. The only difference is the HTTP path and POST data content.

HTTP path could be:

/bag?ix=5&agent=Software%20Update&v=4&os=18.2

This looks like a normal iOS Software Update query. In reality, POST data content is encrypted exfiltrated data.

Or alternatively:

/assets/com.apple.MobileAsset.SoftwareUpdate/com_apple_MobileAsset_SoftwareUpdate/[random-looking-hash].zip

This would appear as if the device is downloading an iOS update package. In reality, it is SENDING data (HTTP POST rather than GET).

Backend Infrastructure:

If such a system existed, it would require secretly managed backend infrastructure. This could be implemented in two ways:

Option A: Compromised CDN Server

A specific CDN edge server or small portion of Apple's infrastructure would be silently modified to redirect certain types of requests to a different backend server. For example, a reverse proxy rule:

IF (HTTP_PATH matches /bag?ix=5 AND

POST_data_size > 1MB AND

Custom_HTTP_header present)

THEN forward to special_backend_server

ELSE process normally

For normal users and network monitoring, everything would appear completely normal. Only requests containing a special "fingerprint" combination would be routed to the secret server.

Option B: Separate Infrastructure

An alternative implementation would use entirely separate server infrastructure configured to respond as if from Apple CDN:

- Register a domain like

cdn-apple-edge.comthat appears credible - Configure DNS name servers to respond like Apple's CDN

- Obtain a valid TLS certificate (or use own CA if baseband trusts it)

The baseband would make a DNS query to this domain (bypassing iOS's DNS cache) and establish a connection directly to this server. iOS would not see this traffic at all because it occurs at baseband level.

This would be riskier because network monitoring could detect connections to non-Apple domains. Therefore, Option A (compromised legitimate infrastructure) would be more likely.

4.3.4 Timing and Traffic Patterns

Data is not sent in large bulks but in small packets that blend with normal traffic.

For example, audio data can be sent in 30-second segments that are encrypted and compressed into approximately 100-200 kilobyte packets. The baseband sends one packet when the device is already communicating with the network anyway:

- When user downloads email

- When user browses the web

- When iOS checks for updates in background

- When iCloud syncs data

This makes traffic analysis extremely difficult because there is no clear pattern distinguishing backdoor traffic from normal traffic. iPhones already make dozens of HTTPS connections to Apple servers every day.

Additionally, the baseband avoids suspicious patterns:

- If user is in airplane mode or offline → nothing is sent, data is queued

- If battery is nearly depleted → transmission is avoided (additional power consumption would be detectable)

- If network is slow or unstable → transmission frequency is reduced

- If user is in roaming network → either transmission is avoided or very small packets are used (large data volumes while roaming could raise suspicions on the bill)

Adaptive Transmission Rate:

The backdoor could analyze the user's normal data usage patterns during the first hours and then adapt its own traffic to match. If the user regularly downloads videos or uses data heavily, the backdoor could send more aggressively. If the user is a conservative data user, the backdoor would send more slowly to avoid detection.

4.4 Protection Against Detection – Multi-Layered Defense

For a hypothetical backdoor to remain hidden for years, it would need to contain multiple layers of defense against various detection methods.

4.4.1 Firmware-Level Obfuscation

Code Integration Among Legitimate Functions:

Rather than having a clearly distinct "backdoor_main()" function, backdoor logic would be distributed across multiple functions that appear to be part of normal baseband functionality.

For example:

- DTMF decoding could be part of normal audio codec function with an additional branch checking for special sequences

- SIP INFO handling could be part of normal SIP protocol code

- Microphone activation could be part of "diagnostics mode" functionality, which is a legitimate feature for testing purposes

Code Obfuscation:

- "Dead code" addition: code that appears to do something but does not actually affect anything

- Control flow complication: arranging if statements and loops illogically

- String encoding: strings stored in encoded form and decoded at runtime

- Opaque predicates: conditions that are always true/false but whose value is not obvious from static analysis

Reuse of Cryptographic Primitives:

The baseband needs AES encryption and RSA signature verification anyway for cellular network authentication. The backdoor would use the same cryptography functions the firmware already contains. Static analysis would only see that "this function calls the AES_encrypt() function," which is completely normal.

4.4.2 Traffic-Level Concealment

TLS Encryption:

All network traffic is TLS-encrypted, preventing content inspection. Even if someone could decrypt TLS (for example, in an enterprise environment with TLS-intercepting proxy), they would see only encrypted binary data in the HTTP POST request body, which could well be part of an iOS update or App Store synchronization.

Use of Normal Protocols:

No strange ports or protocols are used. Everything is standard HTTP/HTTPS (ports 80/443). DNS queries are normal A/AAAA records. TLS handshake is identical to iOS's normal traffic.

Timing Side-Channel Mitigation:

Transmission timing varies randomly to avoid regular patterns detectable by network monitoring. If data is sent on average every 5 minutes, the actual interval varies between 3-8 minutes.

4.4.3 Hiding Power Consumption

The baseband is already active handling cellular network communication, so additional processing from the backdoor does not cause a significant difference in battery consumption. Modern baseband processors are powerful enough that audio encoding and encryption do not require significantly more power than normal 4G/5G modem operations.

Additionally:

- Microphone is activated only during activation state, not continuously

- GPS queries are made at low frequency (e.g., 1 time / 30 seconds) rather than continuous tracking

- Data transmission is timed to moments when baseband is already active anyway (data sync, email fetch, etc.)

4.4.4 Operating System Level Isolation

iOS sees nothing because everything happens at baseband firmware level, which is outside the operating system's visibility.

There is no API that would allow iOS to ask "what is the baseband doing right now" or "show me the baseband's memory contents" or "report all I2C commands the baseband has sent." iOS can send commands to the baseband (e.g., "call this number") but cannot receive reporting about its internal state.

This is a fundamental architectural difference that makes baseband-level threats so difficult to detect with operating system-level tools. There is no iOS application that could detect this backdoor because applications cannot access the baseband layer.

5. iPhone Model-Specific Analysis

Practical implementation of a hypothetical backdoor would depend on which iPhone model it is in and which baseband modem that model uses. This section analyzes how a backdoor could theoretically have been implemented in different eras.

5.1 Foundation: iPhone 4S - iPhone 6s (2011-2015)

This period would represent the establishment and initial phase of a hypothetical project. iPhone 4S was released in October 2011 and was the first iPhone to use a Qualcomm modem – the MDM6610 model. This was a significant transition as previous models had used Infineon modems (which later became Intel).

Qualcomm MDM6610 was a relatively simple 3G modem that supported CDMA2000 and UMTS/HSPA networks. Firmware was much smaller and simpler than modern 5G modems where firmware can exceed 100 megabytes. This would make backdoor integration easier because there would be less complexity in the codebase to hide among.

Technically, MDM6610 was based on ARM9 processor architecture and included a separate DSP processor (Digital Signal Processor) for radio signal processing. A hypothetical backdoor could be placed at DSP firmware level, to which there is even less visibility than main ARM code. DSP executes highly optimized assembler code for signal processing, and its reverse engineering is particularly difficult.

iPhone 5 brought LTE support with Qualcomm MDM9615 modem. This modem brought significantly more complex firmware architecture because it had to support both legacy 2G/3G networks and the new LTE standard. Firmware size grew and a modular architecture emerged where different radio technologies were separate components.

Modular architecture would provide an ideal hiding place for a backdoor. It could be implemented as a "diagnostics module" that would appear to be an engineering tool for testing. Mobile industry devices traditionally have extensive diagnostics modes allowing engineers to test RF performance, signal strengths, and protocol behavior. The backdoor could be disguised as part of this diagnostics infrastructure.

iPhone 5s brought the first Secure Enclave, a separate security processor that handles Touch ID data and cryptographic keys. It is important to note that the Secure Enclave is completely separate from both the main processor and the baseband. It is its own processor with its own firmware and memory. This means that even if the baseband were compromised, it would not directly access the Secure Enclave and thereby, for example, user fingerprints or encryption keys stored there.

This period ended with iPhone 6s, which used Qualcomm MDM9635M modem. At this point, architecture had stabilized and a hypothetical backdoor would have been operational for several years. Firmware updates could have brought small changes to backdoor code, perhaps new features or improvements to concealment, but basic mechanics would have remained the same.

Activation during this era would have been based on rapid DTMF sequences or FSK modulation because VoLTE was not yet widely available.

5.2 Transition Period: iPhone 7 - iPhone X (2016-2017)

This period is extremely interesting from the hypothetical scenario's perspective because it includes the transition where Apple began using two different modem manufacturers simultaneously.

iPhone 7 and 7 Plus were released in September 2016 in two variants. Some models used Qualcomm MDM9645M modem (models A1660 and A1661 sold to Verizon, Sprint, and certain international markets) while others used Intel XMM7360 modem (models A1778 and A1784 for AT&T, T-Mobile, and European GSM operators).

This split strategy created an interesting challenge for a hypothetical backdoor. If the backdoor were only in Qualcomm firmware, approximately half the devices would be without it. Logic dictates that the backdoor would also need to be in the Intel modem.

Intel XMM7360 was, however, a completely different architecture than Qualcomm's MDM series. Intel uses its own firmware architecture based on Intel Atom-based processor for LTE protocol processing and a separate FPGA/ASIC chip (Field Programmable Gate Array / Application-Specific Integrated Circuit) for digital signal processing. Firmware structure is different, using Intel's own development tools and abstractions.

In a hypothetical scenario, the backdoor would have had to be integrated into Intel firmware as well. This would have required either cooperation with Intel or alternatively secretly obtained access to Intel's firmware code and development tools. Another possibility is that Apple itself integrates the backdoor as part of firmware customization they do when taking a modem manufacturer's base firmware and optimizing it for the iPhone platform.

An interesting technical detail is that the Intel version received public criticism for weaker performance. Benchmarks showed that Intel modem models' LTE speeds were approximately 30 percent lower than Qualcomm models in similar network conditions. The official explanation was that the Intel modem did not support all the same LTE features such as 4x4 MIMO or 256-QAM modulation.

iPhone 8, 8 Plus, and X continued with the same split strategy using Qualcomm MDM9655 and Intel XMM7480 modems. These were more advanced versions supporting faster LTE-A (LTE Advanced) traffic and better features, but fundamental architecture remained the same.

This era marked the transition toward VoLTE-based activation. While older methods (DTMF, FSK) were retained for compatibility, new SIP INFO and RTP events methods offered quieter and more reliable activation.

5.3 Intel Era: iPhone XS/XR and iPhone 11 (2018-2019)

In 2018, a significant change occurred: Apple switched to using only Intel modems in all models. iPhone XS, XS Max, and XR used Intel XMM7560 modem. Qualcomm was completely out.

The official explanation was the legal battle between Apple and Qualcomm that began in 2017 concerning patent licensing fees. Apple accused Qualcomm of monopolistic pricing, and Qualcomm countered by accusing Apple of patent infringement. The legal case was complex and touched multiple jurisdictions.

Intel XMM7560 was a significant upgrade from the earlier XMM7480. It supported LTE Category 16 (up to 1 Gbps download) and included broader support for different LTE bands. Firmware was significantly larger and more complex. Increased complexity makes the reverse engineering process even more difficult – when firmware is 80-100 MB compressed and contains tens of thousands of functions, finding a single backdoor function is like searching for a needle in a haystack.

iPhone 11, 11 Pro, and 11 Pro Max (2019) used Intel XMM7660 modem. This was Intel's last modem in iPhone. It was publicly reported that Intel had difficulties with 5G modem development and that Apple was dissatisfied with Intel's roadmap.

5.4 Return to Qualcomm: iPhone 12-16 (2020-2024)

In April 2019, Apple and Qualcomm made a surprise settlement in all their legal cases. The agreement included a six-year licensing agreement and use of Qualcomm chips in Apple devices. Only months later, Intel announced withdrawal from the 5G smartphone modem business. Apple bought Intel's smartphone modem division (approximately 2,200 engineers and 17,000 patents) for one billion dollars.

iPhone 12 series was released in October 2020 and was the first 5G iPhone. It used Qualcomm Snapdragon X55 5G modem. This was a significant leap in complexity – the 5G NR (New Radio) standard is a massive addition to firmware requirements, including beamforming for millimeter-wave frequencies, dual connectivity where the device can be connected to both LTE and 5G networks simultaneously, and significantly more complex MIMO processing.

Qualcomm X55 firmware is estimated to be over 100 megabytes in size and contains millions of lines of code. Such a massive codebase provides ample opportunity to hide additional functionality. Complexity is both a challenge and an opportunity – it makes reverse engineering extremely difficult.

iPhone 13 series used Qualcomm X60 modem, iPhone 14 series X65, and iPhone 15 series X70. Each generation brought improvements to 5G performance, energy efficiency, and features. Firmware continued to grow and become more complex.

iPhone 16 series uses Qualcomm Snapdragon SDX71M modem. This is currently the newest Qualcomm modem on the market and supports 5G Release 17, including features such as reduced capability (RedCap) devices and satellite connectivity capabilities.

5.5 New Era: Apple C1 Modem (2025-)

iPhone 16e, released in February 2025, was historic: it contained the first fully Apple-designed baseband modem, codenamed C1.

This is an analogous transition to when Apple moved from Intel processors to their own Apple Silicon chips (M-series in MacBooks and A-series in iPhones). Now Apple controls the entire chipset design including the modem, providing complete vertical integration.

The C1 modem is manufactured using TSMC's (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company) N4P process (4 nanometer processor technology). It is integrated as part of the A18 SoC and is not a separate chip. This tight integration enables better energy efficiency and performance because baseband and main processor can communicate faster with lower power consumption.

In a hypothetical scenario, Apple's own modem would be both a risk and an opportunity. When Apple controls the entire design, building a backdoor from scratch would require either conscious participation of Apple engineers or the ability to influence the design process at some stage.

But it is also an opportunity to make the backdoor even better integrated. When the same party designs both baseband and main processor, they can optimize the architecture. For example, DMA channels could be designed so that the baseband can efficiently access certain memory regions but this would not appear in external documentation.

Additionally, when firmware is developed from scratch, the backdoor can be architected as part of the base system rather than being "added on top." This would make it even harder to distinguish from other code.

TSMC's role is also interesting. The manufacturing process uses lithography masks that define how transistors are formed on silicon. If a hypothetical backdoor were partially at hardware level (for example, a special hidden register file or memory region), this would need to be included in the lithography masks. TSMC manufactures chips according to Apple's specifications, but it is unclear how deep an analysis they perform on mask data.

6. Detection – Technical Guide

If a hypothetical baseband backdoor existed, how could it be detected? This section describes technical methods a researcher could use to try to find such a backdoor.

6.1 Firmware Analysis

The first and most obvious approach would be direct analysis of baseband firmware. This requires firmware dumping, which in turn requires JTAG debugger access to the baseband processor.

JTAG Access and Firmware Dumping:

JTAG (Joint Test Action Group) is a standardized debug interface used for hardware testing and debugging. Almost all modern processors have JTAG ports enabling direct memory access, register reading, and code stepping. For security reasons, JTAG ports are often disabled in production devices, but physical pins are still on the PCB.

iPhone disassembly is the first step. This requires special tools such as iSlack (suction cups for display removal) and extremely fine screwdrivers. The baseband modem is located on the motherboard, and its identification requires studying datasheets and reading chip markings under a microscope.

Next, the researcher must identify JTAG pins. These are usually not clearly marked but require probing with a multimeter and searching for schematic diagrams. In some cases, micro-soldering (working under a microscope) is needed to attach wires directly to chip pins.

Once JTAG connection is established, the researcher can use tools like OpenOCD (Open On-Chip Debugger) or JLink software to communicate with the processor. The first task is firmware dumping – copying the entire flash memory contents to a file for analysis.

Dumping is not necessarily trivial. Some modern processors have "read protection" that prevents firmware reading via JTAG. Bypassing this may require physical attacks such as voltage glitching (momentary voltage drop causing processor error state) or laser fault injection (using a laser to temporarily corrupt memory cells).

Reverse Engineering:

Once firmware is dumped as a file, reverse engineering begins. The first step is disassembly – translating machine code to assembly language. Tools like IDA Pro, Ghidra, or Binary Ninja are industry standards for this. They automatically identify functions, create code flow graphs, and try to identify library functions.

But baseband firmware is huge: tens or hundreds of megabytes and millions of assembler instructions. Simply browsing through is impossible. The researcher must use heuristics to search for interesting areas:

Searching for Cryptographic Functions: AES and RSA algorithms have identifiable code patterns: certain operations like S-box lookups in AES or modular exponentiation in RSA. Tools can scan firmware for these patterns. Once a crypto function is found, the researcher can trace who calls it and for what purpose.

String Searching: Even if firmware is obfuscated, it likely contains some error messages, debug prints, or other texts. Searching for odd strings could find clues. Of course, if the backdoor is well-designed, obvious strings have been removed or obfuscated.

Function Size Analysis: Most functions are relatively small – from a few dozen to a few hundred instructions. If there is a very large function containing thousands of instructions, it may be complex and possibly hiding unusual logic.

Firmware Version Comparison: If updated firmware is available for multiple iPhone models, diff analysis can be performed to see what changed. Most changes relate to bug fixes or new features, but anomalies could reveal hidden code.

6.2 Live Testing and Signal Analysis

Another approach is to test device usage in a live environment and look for unusual behavior.

Activation Testing:

The researcher builds a fake base station device using software-defined radio (SDR) hardware such as USRP (Universal Software Radio Peripheral) or BladeRF combined with software like OpenBTS or srsRAN that implements GSM/LTE base station logic.

The fake base station is configured to appear as a normal cellular network. The iPhone is connected to it (inside a Faraday cage so real networks are not disturbed). Then the researcher calls the iPhone, and when the call is answered, sends the suspected activation sequence – either rapid DTMF, FSK data, or in VoLTE environment, SIP INFO message.

Baseband Processor Monitoring:

If JTAG connection is active, the researcher can set breakpoints – stop points that halt code execution at a certain address. If the baseband suddenly jumps to an address not normally used, this could be a sign of activation.

Power Consumption Analysis:

Power supply to the iPhone is routed through special equipment measuring current continuously at microampere precision. If the baseband starts a new processing operation, power consumption changes. Side-channel analysis uses such physical properties to infer what the processor is doing.

RF Signal Analysis:

The researcher uses spectrum analyzer equipment to monitor what radio signals the iPhone transmits. If the backdoor activates and starts transmitting encrypted data, this appears as increased RF activity on certain frequencies. While content cannot be read, RF activity pattern analysis may reveal unusual behavior.

Network Traffic Capture:

The researcher configures the iPhone to operate through a proxy server that logs all HTTP/HTTPS traffic. While TLS encryption prevents reading content, metadata is still visible – which IP addresses connections are made to, when, how much data is transferred.

If the backdoor sends data, it would appear as increased traffic. The researcher could compare normal iOS usage (without activation) and post-activation situation to see if traffic patterns differ.

TLS-Intercepting Proxy:

In enterprise environments, a custom root certificate can be installed on the iPhone enabling man-in-the-middle position for HTTPS traffic. This enables inspection of encrypted traffic. If the researcher does this, they could see exact HTTP requests including paths and POST data.

However, it should be noted that if the backdoor is truly well-designed, it may detect TLS interception (because the certificate is not Apple's original) and deactivate itself to avoid detection.

6.3 Comparative Analysis Between Different Models

An effective way to search for anomalies is to compare multiple devices and models against each other.

The researcher could obtain, for example, ten different iPhone models from different generations (4S, 5, 6, 7, X, 12, 14, 16) and perform identical test sequences on each. If all devices behave the same way under certain conditions but one model differs, this requires deeper investigation.

Comparative analysis of baseband firmware between different models could reveal common code patterns. If there is a certain function that is identical from iPhone 5 to iPhone 16 but is not documented, it is suspicious. Normally firmware evolves over time and old functions are replaced with new ones. If some code remains unchanged, it suggests it is a critical part of the architecture that is not meant to be changed.

The researcher could also compare the same model in different market regions. For example, iPhone 7 has versions for the United States (A1660/A1661), Europe (A1778/A1784), and China (A1660). If firmware differs between these in ways other than expected (just radio frequency differences), it could indicate region-specific modifications possibly for political reasons.

6.4 Challenges and Limitations in Detection

It is important to acknowledge that detecting a well-designed baseband backdoor is extremely difficult, even with significant resources. There are several reasons for this.

Firmware is massive and complex: Complete analysis would require years of work from a team of experienced reverse engineering experts. This is impractical in terms of time and funding for most researchers or even universities.

Protection mechanisms: JTAG ports are disabled, read protection is active, and firmware is cryptographically signed. Bypassing these requires specialized expertise in the hardware hacking field.

Active resistance: If the backdoor truly exists and there are parties aware of it who want it to remain secret, they may actively try to prevent detection. The researcher may face pressure to stop: legal threats, loss of funding, or in worst cases, personal threats.

Burden of proof: "Proof of non-existence" is nearly impossible. Even if the researcher analyzed firmware thoroughly and found nothing suspicious, it does not prove the backdoor does not exist. It may just be so well hidden it was not found. This is a fundamental epistemological challenge in all security research.

7. Conclusions and Implications

7.1 Technical Feasibility and Real Evidence

Based on this analysis, a hypothetical baseband-level backdoor is technically feasible. All mechanisms described in this document are based on real technology and known protocols. There is nothing "magical" or contrary to physical laws in any part of this hypothetical system.

But this is no longer mere theory. As described in section 4.2.4, we have access to documentation strongly suggesting such a system actually exists and is actively in use. The described case is not our only observation, but it is sufficiently documented and verifiable that we can share it publicly.

This fundamentally changes the nature of the analysis. We are no longer asking "could this be possible" but "how does this work and how can we protect ourselves from it."

Critical feasibility elements now confirmed by real observations:

Baseband processor's special position: Because the baseband operates outside operating system visibility and handles all radio communication, it is an ideal location for a backdoor. iOS cannot monitor or restrict baseband operation in any significant way. This is no longer mere theory: we have observed behavior consistent with this.

Call-based activation mechanisms: VoLTE SIP INFO messages provide a completely undetectable way to send activation commands. This case demonstrates that an ordinary call can be used for activation in a way that does not arouse user suspicion.

Apple C1 modem compromise: Particularly concerning is that observations involve the iPhone 16e model using Apple's first fully self-designed C1 modem. This signifies that if a backdoor exists, it is not limited to external modem manufacturers' (Qualcomm, Intel) products but extends to Apple's own design as well. This is a significant revelation suggesting the backdoor is built as part of baseband's fundamental architecture and is not just a legacy feature from older modems.

Firmware signing: Although firmware is digitally signed, this does not protect if the signing party (modem manufacturer or device manufacturer) itself includes the backdoor. Signing only ensures firmware comes from the right party – not that it is benevolent.

Activation mechanisms: Call-based activation mechanisms are realistic, especially in the VoLTE era. SIP INFO messages provide a completely undetectable way to send activation commands and receive confirmations.

Data exfiltration: Masquerading among legitimate traffic is a proven working technique. When the backdoor uses the same protocols, same servers, and same encryption practices as normal traffic, distinguishing it is extremely difficult.

7.2 Historical Precedents

The Crypto AG and Dual EC DRBG cases demonstrate that:

- Hardware-level backdoors can remain hidden for decades

- Standardization processes can be manipulated

- Large-scale institutional support enables long-term operations

- Technical complexity protects against exposure

Baseband firmware meets all the same criteria that made these historical cases successful long-term operations.

7.3 Challenges in Defense

Ordinary users have practically no means to detect or protect against a hypothetical baseband backdoor. All normal security measures – VPNs, end-to-end encryption, security software – operate at operating system level and are ineffective against threats implemented at baseband level.

Even technically sophisticated users face significant challenges:

- Firmware analysis requires specialized equipment and years of expertise

- Live testing requires expensive SDR equipment and deep understanding of telecommunications protocols

- Network monitoring is ineffective due to TLS encryption and legitimate traffic masquerade

7.4 Broader Societal Implications

If such a backdoor existed, its effects on privacy and society would be profound:

Privacy breakdown: Every call, message, location, and digital activity could be subject to surveillance without the user having any way to know or prevent it.

Trust erosion: If a baseband backdoor were exposed, it would shake trust in all technology companies and devices. How could anyone trust any device going forward?

Power imbalance: Access to such surveillance capability creates enormous imbalance between those with access to the system and those without.

7.5 Recommendations for Improving Transparency

While this analysis is speculative, it raises real challenges in baseband security. The following measures could improve the situation:

Open-source baseband firmware: A fully open-source baseband firmware implementation would enable independent auditing. Projects like Osmocom have begun this work but have not yet achieved commercial viability.

Independent auditing: Manufacturers could allow independent security companies to audit baseband firmware regularly. This would require confidentiality agreements but would increase transparency.

Hardware-level isolation: Physical isolation of baseband from main processor and stricter IOMMU restrictions would reduce the impact of a compromised baseband.

User-level monitoring: Developing tools that give users better visibility into baseband operation – for example, when microphone or GPS is active at baseband level.

Firmware transparency: Public changelog documents for baseband firmware updates with detailed explanations of what changes were made and why.

7.6 In Conclusion – Why This Document Exists

This analysis is no longer mere speculation. It is documentation of a real threat affecting millions of people around the world, including users of the latest iPhone 16e model who may think Apple's own C1 modem makes their devices safer.

We are publishing this document for several reasons:

First, responsible disclosure. We have access to material strongly suggesting the existence of this threat. We can either keep it secret, which helps no one, or share the information in a way that helps the security community and ordinary users understand the risk. We have chosen the latter.

Second, documentation preservation. This analysis and related evidence has been securely stored in multiple locations.

Third, security community activation. We are not the only ones who can research this. By publishing technical analysis, we provide tools and methods for other researchers who want to confirm or refute our findings. The more people research baseband security, the harder it is to keep potential backdoors hidden.

Fourth, political and societal discussion. This is not just a technical question but a fundamental question about privacy, surveillance, and who holds power in our society. If baseband-level surveillance is possible and in use, society must decide whether this is acceptable and under what terms.